The traditional ornamental lathes (built in the 18th and 19th centuries) were elaborate machines with pulleys, cams, gears, belts, etc.

The resulting complex machines were so expensive, that only the "nobility" could afford them.

Thus, ornamental turning was often called the "hobby of nobility".

Today, with modern materials and new innovations, we can construct very precise machines at a very reasonable cost.

My current machine is my own design and is controlled by a computer.

I'm convinced that if computers, stepper motors, and linear bearings were available in the 18th and 19th century,

the designers of that time would have used them instead of the more complex mechanical "analogs".

This is not a machine for mass-producing a number of identical pieces.

Instead, the design is intended for the artist making one-of-a-kind artwork.

Update April 2020

I'm mostly retired from woodturning.

The information here is provided for inspiration to those who choose to

follow a similar path.

Some of the information is a bit dated (valid at the time I built my machine) and may

not be the best for new projects that you might be starting now.

I have no current plans to make any significant upgrades and/or changes to my existing shop hardware.

Likewise, I don't plan on doing any new work on the software.

(If it works, don't fix it).

In particular, I don't have any plans to update the software to newer versions of the MacOS

or newer versions of Java.

The source code is available to those

who want to make such improvements for themselves.

Design Goals

After making my first traditional rose engine lathe (MDF Rose Engine),

I quickly became aware of many limitations.

The goals for this current machine were as follows:

-

Turn the shape on the same lathe as the OT work so that you don't have to correct for errors moving

from one machine to the other.

This means a firm method of locking the head (and driving the spindle with another motor)

or it means moving the cutter instead of moving the head.

-

Linear movement (not rocking in an arc) so that cutting on the front or on the back does not have alignment problems.

This means linear bearings instead of a pivot point.

-

Pumping and Rocking motions (or both together), and pump from any pattern.

-

Flexibility to change amplitude, phase, number of repeats of the pattern per revolution, and index any number easily.

At this point, it becomes attractive to consider a computer with stepper motors moving the slide.

-

Easy to add a new pattern.

Again, this points to a the flexibility of a computer.

-

Ability to make various styles of spirals.

Although there are ways of doing this in mechanical hardware, it becomes much easier in software.

-

Ability to follow the shape of a hand-turned profile.

Again, the mechanical approach is challenging and seems easier to do in software.

-

Utilize modern materials.

-

A flexible tool for art, not a mass production machine.

-

Simple hardware (although the software will be complex).

-

Affordable. This leads to scrounging on eBay for the hardware.

-

Easy to go from the creative vision to cutting the wood.

This includes the ability to simulate the final appearance of the item prior to cutting.

This saves time (i.e. not having to practice cuts a lot) and allows for rapid discovery of new pleasing patterns.

Solution:

Computerized Ornamental Lathe (COrnLathe™)

An x-y stage (eBay) with stepper motors, mounted on a mini-lathe (Jet 12x20)

and driven by an inexpensive computer (Mac mini used from eBay).

I started working on this project in January, 2009.

By May, 2009 I had the basic concept working (i.e. I convinced myself this was going to work).

By January, 2010 I had the machine (and the software) mostly functional and could start using it to make things.

I was detoured by the need for better cutting frames (see the Cutting Frame page for more details).

Since then, I continue to evolve and improve the software, but have spent a lot of time doing fun creative work.

My stage has 6" x 6" of travel and 0.05 mil resolution.

The stage can quickly be removed from the bed of the lathe for regular turning.

To go from a regular lathe to the OT mode, slip a belt off the stepper motor and slip on the belt to the main lathe motor.

Also, the stage can be mounted either on the back side of the work or on the bed of the lathe,

depending on the direction of cuts being done.

The electronics is all mounted on the stage -- the only wires are a single USB cable to the computer,

a power supply connection, and wires to the spindle stepper motor.

Movement can be manually controlled using a dials (rotary manual pulse generator).

Recently, I've taken the time to document the details of my current machine.

I don't make machines or offer them for sale.

The details are made available to aid anyone else who wants to learn from my experience and build their own machine.

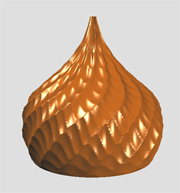

Perhaps the most significant contribution I've made to the state-of-the-art is the ability to

simulate the 3D appearance of an object on the computer.

This has a very dramatic effect on one's ability to conceive of new shapes and patterns.

I can move the position of a cut by dragging on the mouse, and immediately see the result of all the cuts together on the screen.

The 3D modeling software is now being made available to other wood-turners.

For more information, see the COrnLathe Software page of this web site.